- Source: PHAIDON

- Author: PHAIDON EDITORS

- Date: OCTOBE 26, 2017

- Format: DIGITAL

Vitamin C: Anders Ruhwald – Why I Create

Exploring the inspirations and attitudes of artists working with clay and ceramic

Anders Ruhwald in his studio

Sculptor Tony Cragg’s phrase ‘When I move, the clay moves’ is one that Anders Ruhwald is rather fond of. The Danish born US resident is noted for large-scale installations that explore ceramic as both idea and material. He brushes aside the distinction between art and craft, emphasizing instead the disruptive and transformative capacity of objects in space. Ruhwald refers to himself as “a form-giver: An artist who thinks through materials using the language of form and space.” An emphasis on ceramics as a vehicle for selfhood is apparent in his work. Playing with ideas through the language of decorative arts is typical for Ruhwald, for whom the messy practicality of objects is something to be embraced, not occluded. Rarely appearing on plinths, his forms occupy a place equidistant from sculpture and design.

Here, the Vitamin C: Clay and Ceramic in Contemporary Art featured artist tells us why he works in the medium, what particular challenges it holds for him and who he thinks always gets it right.

Bowl (Black Hole) – Version A & B, 2013 – Anders Ruhwald

Who are you and what’s your relationship to clay and ceramics?

I am a Danish born artist, who for the past 10 years has lived and worked in Detroit. In my practice I work with clay mainly. Sometimes I make installations other times I make objects. Sometimes I make objects that go into installations. Sometimes I make installations that are made of objects.

I have always found it difficult to describe my practice in a few sentences. It seems to me that the description will change depending on when I am asked and where I am at in a specific cycle of organizing and making. I have worked with ceramics since I was 15 and understand the mechanics of the clay process intuitively. It is a material that I use to think with. I think of it as an extension of the body – a material onto which I can record movement and intention.

To me the physical presence of the work is an essential element and ceramics has amazing properties to convey this. The materiality, weight, scale, balance, surface, colour, and at times the smell of the work is crucial to the reading of the work. At best I would like the work to insert itself into the world and be present as any other everyday object might be. I care less about representation. The work needs a material presence and an ability to communicate directly because I would like the reading of the work to happen as much with the mind as it does with the body.

I spend a lot of time configuring the placement of work and try to anticipate how an audience might move through spaces and experience the work. This is why I sometimes make full installations and other times only place objects into existing environments. Placement and context offers an opportunity to frame the work and suggest at the ideas that inform them.

My Nose as Seen With my Eyes – Version A & B, 2013 – Anders Ruhwald

Why do you think there’s an increased interest around clay and ceramics right now?

I think the interest in ceramics is kind of ebb and flow. When I stumbled on ceramics in the early 90s, it was mainly seen as a joke. By choosing to work with this material, I found I had to explain myself a lot – often to skeptics, who couldn’t see merit to the material or its history. But over the last 10 years this has changed drastically with a younger generation interested in intuitive and idiosyncratic materials to explore ideas with.

But I think it is important to acknowledge the history of ceramics as continuum. It may fall in and out of fashion – just as any other medium/field. But to disregard its significance at any point in history is to deny a significant part of art history.

The current resurgence of ceramics I think is no coincidence. Since the early 2000s there have been a concerted effort to restate the history of ceramics including exhibitions like “The Secret History of Clay” at Tate Liverpool and “Dirt on Delight” at the ICA in Philadelphia and at the same time there has been a slew of publications by art historians, artists and curators on ceramics that have traced the lineage of ceramics through art history, asserting its importance especially in regards to 20th century art movements. All of this has helped to bolster the general understanding and appreciation of the material and the history that goes with it.

Ceramics is sometimes regarded as decorative, rather than fine art. Does the distinction bother or annoy you?

I honestly don’t care too much about these distinctions. I like to think of myself as a form-giver: An artist who thinks through materials using the language of form and space. Hereby I can access the histories of decorative art, craft as well as art and design – there is so much grey area between these fields and much of my work arrives in these inbetween spaces.

The Charred Room, 2016 Installation view, ‘Unit 1: 3583 Dubois’ exhibition, MOCA Cleveland, Ohio – Anders Ruhwald

Whose work in this field do you admire?

I am not super concerned with how a thing is made. The challenge of making doesn’t drive my work or how I see the work of others. The technical stuff simply needs to be resolved or worked around. Two bodies of work I keep coming back to are Ken Price’s Happy Curious from the 70s and Nobuo Sekine’s Phase of Nothingness series. The Happy Curious work is such an amazing digression on tourism, cultural appropriation, regionalism and how this might be digested within a context of art. People mostly seem to appreciate Price for his seductive colourful sculpture, but this work shows the real depth that lies behind that later body of work. With the Happy Curious work he was able to access this other history of ceramics that is about the everyday, the souvenirs, the cultural signifiers and how all of this got consumed through the latter part of the 20th century.

Sekine’s Phase of Nothingness series as a body of sculpture sits on a very different spectrum which gets into the core of material presence. There is this one piece from the series, which is essentially a large lump of black clay placed in the gallery which the audience can leave their imprints on. The clay never dries so the piece continues to change as the audience comes through. It’s super simple, but the piece and this whole series of work continues to resonate with me.

What are the hardest things for you to get ‘right’ and what are your unique challenges?

In terms of ceramics, it continues to change. In terms of my work overall this question really depends on the individual piece/project/installation. I don’t know where to start and I continue to question if I ever get anything right. I think the unattainability of ‘rightness’ is what gets me into the studio every day.

What part does the vulnerability of the material play in things?

I think the fragility of the material often gets overplayed. Many hard materials are breakable. It’s not a unique quality of clay or ceramics, nor is it by any standard the most fragile.

Is how you display a piece an important element of the work itself? Do you ever suggest how something might be displayed?

I am interested in how an object can change meaning with its context and I use this as a conscious exhibition strategy. With some of my bodies of work I will display the same object in a vastly different way when I show it at a new space/context.

I think the object accumulates meaning from its surroundings, where it is shown and what it is placed close to. I will talk to curators about how I see the work and where it has arrived from, but am equally interested in understanding how others might read the work and understand it in relation to its surroundings.

I make work to try to understand the world I live in and so meaning isn’t fixed with an object – instead it is continually evolving. I think objects are sites for discussion or questions – the ambiguity of form disallows any static meaning to be set. I have very clear intentions as to why I have made a work. But I am also very aware that this is just how I see it and would like it to be seen – the fact is that the trajectory of this object may end up different to how I imagined it.

I have this ongoing series of images on how collectors have chosen to live with my work in their homes/collections. Here the work is mostly charged with a very different set of circumstances to gallery/biennial/museum context. It is both part of an everyday life, but also tied into this larger grid of the uniquely personal and intimate. It interests me.

What’s next for you, and what’s next for ceramics?

In the fall, I hope to complete a large scale installation called Unit 1: 3583 Dubois inside a Detroit apartment. It’s a seven room immersive installation where I have transformed the entire interior of the apartment. The installation circles around the idea of fire as an agent of chance in relation to the city, the domestic and the intimate.

I have been working on this piece for the last four years and I aim to wrap it up this fall, so I can begin to get people through the space. Over the winter I will be working on a new body of work to be shown at Casa Jorn in Albisola, Italy next summer – which is the house and studio of the Cobra painter Asger Jorn on the coast of the mediterranean. But Albisola is also where the Futurists did their ceramics and Fontana had one of his studios. There is a wild history with this village and so I am looking forward to digging into this.

As for ceramics more broadly, I have no clue. There is so much happening with the material right now and it engages me. Time will tell if its just a phase or if this really is a sea-change for the medium. It will keep on keeping on in my studio either way.

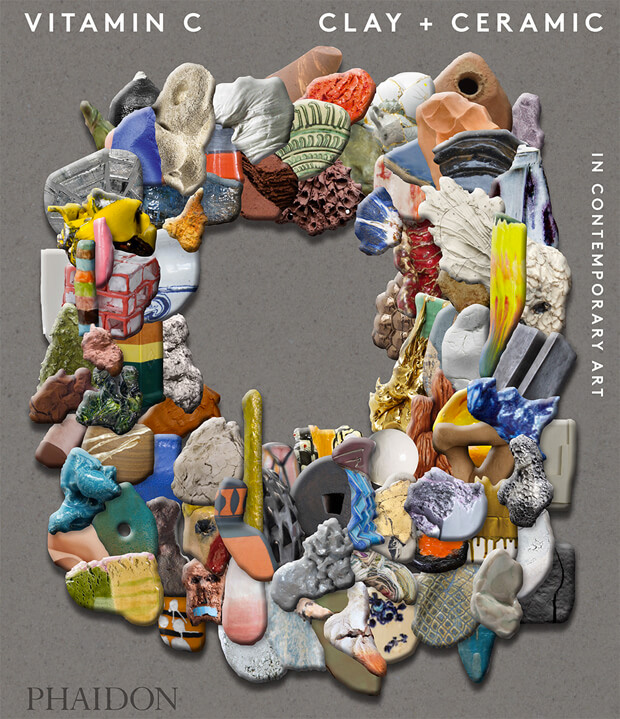

Clay and ceramics have in recent years been elevated from craft to high art material, with the resulting artworks being coveted by collectors and exhibited in museums around the world. Vitamin C: Clay and Ceramic in Contemporary Art celebrates the revival of clay as a material for contemporary artists, featuring a wide range of global talent selected by the world’s leading curators, critics, and art professionals. Packed with illustrations, it’s a vibrant and incredibly timely survey – the first of its kind. Buy Vitamin C here. And if you’re quick, you can snap up work by some of the artists in it at Artspace here.